A Chilling Photograph’s Hidden History

Twenty-six years ago, a picture of an execution in Iran won the Pulitzer Prize. But the man who took it remained anonymous. Until now. The Ayatollah’s agents come calling.

December 6, 2006, The Wall Street Journal

TEHRAN — On Aug. 27, 1979, two parallel lines of 11 men formed on a field of dry dirt in Sanandaj, Iran. One group wore blindfolds. The other held rifles. The command came in Farsi to fire: “Atesh!” Behind the soldier farthest to the right, a 12th man also shot, his Nikon camera and Kodak film preserving in black and white a mass execution.

Within hours, the photo ran across six columns in Ettela’at, the oldest newspaper in Iran. Within days, it appeared on front pages around the world. Within weeks, the new Iranian government annexed the offending paper. Within months, the photo won the Pulitzer Prize.

Taken seven months after Islamic radicals overthrew the U.S.-backed Shah, the photo remains one of the most famous images of Iran. It is an icon of government terror, invoked in critiques of the regime from the 1979 poem “Screaming,” to the 1986 music video “Speak To Me From My Land, Iran” to the 1997 book “Kurdistan.” Davood and Davar Ghassemlouie, brothers who operate a photo shop in Los Angeles, say they have made tens of thousands of reprints for demonstrators, including 200 in late September when Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad visited the U.S.

Says Shahrokh Hatami, a pioneer of Iranian photojournalism: “It is the most revealing photograph of the beginning of the Iranian revolution.”

Ettela’at, however, didn’t print the photographer’s name, fearing his safety. The Pulitzer was officially awarded to “an unnamed photographer of United Press International,” the news service that distributed the photo in the U.S. It remains the only time the award has ever been given to an anonymous recipient.

In the years since, several people have falsely claimed to be “Anonymous.” When Iran’s most famous photographer died in 2003, his obituaries were filled with mentions of a Pulitzer some say he had insinuated winning. Last September, another prominent Iranian photographer living in France was quoted in Paris Match magazine claiming credit for the work.

In fact, nearly three decades after the epochal photograph first appeared, almost no one knows who took it.

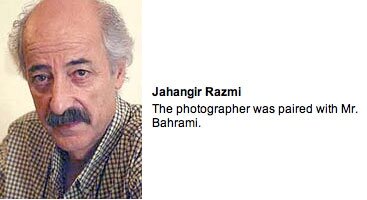

Jahangir Razmi grew up in the industrial city of Arak, in central Iran, the first child of a housewife and military clerk. Governed by the Shah, the nation was at peace. The boy was shy and happiest in a local photo shop helping a cousin develop film and shoot portraits of brides and soldiers. In 1960, at the age of 12, he bought a Russian Lubitel-2 camera.

He quickly put it to use. When one day a boy shot a girl dead outside his studio, a reporter urged Jahangir to photograph the scene. He did, the skirt and shirt of a bloodied school uniform preserved in the newsprint of Ettela’at.

When his father died, Mr. Razmi says he found work in a Tehran photo shop. When he served in the army, he found reprieve from military drills in a darkroom on base. When he photographed a 20th birthday party, he found a wife. And when Ettela’at — Farsi for “Information” — hired him in 1973 to shoot breaking news, he found a career.

“Although we were colleagues and there was a competition, his pictures were better,” says Jafar Danyeli, then one of seven staff photographers. Razmi, as everyone called him, paid attention to composition and chiaroscuro, the interplay of light and shadow. He sat at the desk closest to the stairwell. “I was always the volunteer to go,” says Mr. Razmi, then 25. “I was quick. I was young. I was braver than anyone else.”

On Jan. 16, 1979, the Shah fled Iran following mass demonstrations protesting his rule. Sixteen days later, Ayatollah Khomeini, a radical Islamic cleric, returned from France and seized control. Mr. Razmi photographed Mr. Khomeini in his Qom headquarters so regularly that he came to greet the imam with a handshake. Using his favorite Nikon lens, a 28mm wide-angle lens with automatic exposure, Mr. Razmi chronicled the conversion of Iran to theocracy from autocracy.

By August, about 500 alleged counter-revolutionaries and officials of the former regime had been executed. The judiciary decreed it illegal to criticize Islam and Iran’s spiritual leaders. A holding company formed by the regime appropriated Kayhan, the only newspaper in Iran larger than Ettela’at. Journalists who pushed back at censorship under the Shah were petrified.

“Under Khomeini they would kill you,” says Amir Taheri, then editor of Kayhan and now a political analyst living in England. “It was a different ballgame.”

On Aug. 16, Mr. Khomeini called on Iranian troops to suppress restive Kurds hoping for autonomy. Thousands of soldiers headed 300 miles northwest to the Iranian province of Kurdistan. Mr. Razmi and Khalil Bahrami, an Ettela’at reporter, followed.

Ten days later, Mr. Bahrami received a tip that a judge he had befriended was set to try Kurds in an antechamber of the municipal airport at Sanandaj, the capital of Kurdistan. The reporter, then 37, had worked at Ettela’at for 22 years and was thankful he was paired with the young Mr. Razmi, whose father had lived in Sanandaj and had raised his son to admire the Kurds and their traditions. “He knew his responsibility,” says Mr. Bahrami, who lives in Iran and is retired. “And he was quicker than the others.”

At the airport, Mr. Razmi stood ready outside the makeshift courtroom as 10 handcuffed men filled a wooden bench before the judge, a black-bearded Shiite cleric named Sadegh Khalkhali. An injured 11th prisoner lay on a stretcher beside the door.

The judge removed his turban, Mr. Bahrami recalls. He removed his shoes. He put his feet on a chair. Scanning the prisoners through thick eyeglasses, he asked their names. Officers of the court told of the defendants’ alleged crimes — of trafficking arms, inciting riots and murder. The prisoners, some with leftward or nationalist leanings, denied the accusations.

No evidence was presented, Mr. Bahrami says. “It was pure speculation.” After roughly 30 minutes, Mr. Khalkhali declared the 11 men “corrupt on earth” — mofsedin fel arz — the Koranic phrase he cited before issuing a sentence of death. A few of the men cried.

Mr. Bahrami summoned his colleague Mr. Razmi. “It was Razmi’s luck that day that he was with me,” the reporter says.

Mr. Razmi withdrew from his green canvas shoulder bag a 35-80mm lens and attached the zoom to his Nikon FE. The handcuffed men were blindfolded. Each put his hand on the shoulder of the man before him and together they walked single-file through the airport’s concrete lobby, through a metal doorframe and toward an open airfield. Mr. Razmi darted ahead and shot, untroubled by security forces: “I was totally free,” he says. Unbeknownst to Mr. Razmi, a soldier present also was taking pictures, which were never published.

The caravan passed roughly 30 airport workers, both men say. Up front walked Mr. Razmi. In the rear, both men say, was Ali Karimi, one of the judge’s bodyguards, wearing white shoes, white pants, white shirt, sunglasses and twin hip holsters. After about 100 yards, an officer halted the condemned on a plain of dry dirt. All but one of the executioners tied about their own heads Iranian shawls called chafiyehs. Both the faces of the Shiites and the eyes of the Kurds were now concealed.

Mr. Karimi asked the prisoners if they had last words, the two journalists recall. The men didn’t, all silent save a man Mr. Bahrami later reported to be Essa Pirvali, who wept aloud. A sandwich maker, he belonged to no political party but possessed a handgun and had been accused of murder. “He was scared,” Mr. Razmi says. “He wouldn’t stand.” The soldiers instructed a fellow prisoner to hold him.

An afternoon sun shone behind the prisoners and Mr. Razmi reached for his 28mm lens. He sidled in behind members of the firing squad, who stood in brown leather boots laced to the calf. He thought, he says, only about “speed and angle.” The prisoners stood in plainclothes. The firing squad crouched in camouflage.

“Afrad mosallah!,” yelled the commanding officer, calling his troops to attention. His charges aimed their G3 rifles at the midsections of the men standing little more than a body’s length away.

Standing farthest to the right, Naser Salimi, an employee of the Sanandaj health department, raised his right hand to his chest. It was bandaged, injured in a street fight that had led to his sentencing, according to contemporary newspaper reports. Opposite him, the only soldier who wore no chafiyeh raised his rifle.

Mr. Razmi stood a few feet behind this unmasked gunman. He raised his camera. At 4:30 p.m., the command came to fire: “Atesh!” Eleven guns discharged. Eleven bodies dropped. “When they fell, it was dusty,” Mr. Razmi says. The photographer lowered his camera.

The soldiers eyed Mr. Karimi, the judge’s bodyguard, lifting a pistol off his right hip. Not all of the men were dead, the photographer recalls. The bodyguard leaned over Ahsan Nahid, the injured prisoner on the stretcher, and fired one bullet into his head. Mr. Razmi snapped his Nikon. Mr. Karimi stepped to the next man and shot him, too. He proceeded along — one bullet per body, both journalists say. (Recent efforts to locate Mr. Karimi were unsuccessful.)

WITHIN MINUTES, ambulances ferried away the 11 bodies, airport workers returned to work, the huddle of soldiers thinned and Mr. Razmi stowed his two rolls of Kodak 400 film in a pocket of his canvas bag. After a helicopter flight landed the pair too late to cover a second execution, Mr. Razmi left his colleague, flagged a passing minibus and returned to the airport in Sanandaj, where at 8 a.m. the only daily flight to Tehran departed.

The photographer fell asleep. He was awakened at a checkpoint by shouts from airport officers, the same men who had shared their lunch with him the previous afternoon as they awaited the Kurdish prisoners. “It’s me!” yelled Mr. Razmi. “Jahangir!” The men held their fire. Mr. Razmi told them he had film and an article that had to get back to Tehran. “I put it in an envelope and gave it to the flight attendant,” he says, needing to continue his work in the region.

Mr. Razmi called Ettela’at, which dispatched a courier to the airport. The man picked up the white envelope from Tehran airport and delivered it to the newspaper. Ali Akbar Moradi, head of the paper’s darkroom, says he knew the 70 exposures were taken by Mr. Razmi and that he turned them into two contact sheets with the help of a technician. An office runner gave them to the photo editor, the late Fereydoun Ebrahimzadeh, who marked the frames he wished turned into prints and delivered them to Mohammed Heydari, the chief Ettela’at editor, Mr. Heydari says.

Mr. Heydari was examining the layout of that day’s front page and flipped through the stills. At about noon, he says, he stopped, overwhelmed by a single image of the moment when some of the squadron had fired and some hadn’t. Bodies fell. Dust rose.

Mr. Heydari, then 35, had little time to think — the afternoon paper was about to go to print. He says he told himself that the country was conflicted over the killing of the Kurds and angry over censorship. He decided to publish the photograph, although not in the edition distributed in the Kurdistan province, where it would be tantamount to a call to arms. “Considering the political climate, I knew I could get away with it,” Mr. Heydari says.

The Ettela’at editor made another snap decision. The photograph would run with no credit. “I was aware that if I published his name, he would be in danger,” Mr. Heydari says. “I wanted to protect Razmi.”

By 2 p.m., newsstands across Tehran trumpeted word of the Kurdish executions. The banner headline read: “Forty People Executed in Sanandaj, Marivan and Saqqez.” The accompanying photograph was a sensation, the seven months of Iranian firing squads distilled to one image.

Copies of Ettela’at sold out and representatives of international news agencies hustled to Khayam Street to buy prints. The photo editor, Mr. Ebrahimzadeh, “sold it to everyone like he was selling French fries,” says Alfred Yaghobzadeh, 47, then a photographer for the Associated Press, now a photojournalist based in France.

The first to arrive at Ettela’at was Sajid Rizvi of United Press International. Mr. Rizvi, then 30, had seen the newspaper at his home, ordered a copy by phone and sped off in the company’s pistachio-colored sedan. He picked up the photo roughly 15 minutes later inside the Ettela’at newsroom.

“It was almost wet when I took it,” says Mr. Rizvi, now editor of an arts publishing house in London. “I don’t think I have ever seen a picture as moving as that,” he says. “It is a picture between life and death.”

Mr. Rizvi asked who had snapped it. “They said, ‘better not to give out the name of the photographer.’ ” Once home, he walked into the bathroom he had converted into a darkroom, dried the photo with a hairdryer, composed a caption on his yellow Olympus typewriter, phoned the UPI desk in Brussels and transmitted the print.

Genghis Seren, a photo editor in Brussels, sat transfixed beside the company UniFax. “The drama of that machine was that the picture took 15 minutes to complete,” recalls Mr. Seren, then 25 years old and in his first year at UPI. “It came a 10th of an inch after a 10th of an inch…. It was something!” Mr. Seren forwarded the photo to UPI bureaus in Africa, Europe and the Middle East, and to company headquarters in Manhattan.

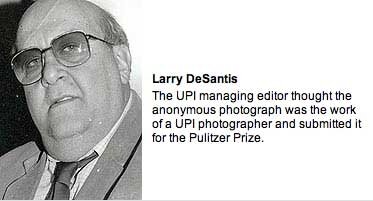

“It was transmitted to us with no name,” says Larry DeSantis, the UPI managing editor who received the photo 11 stories above 42nd Street. “Not knowing who made it interested me.”

At about 3 p.m., several armed agents from the Islamic Revolutionary Council arrived at Ettela’at, ascended four flights and entered the office of the editor, Mr. Heydari. They asked for the negative of the photo and asked to speak with the photo editor, Mr. Heydari recalls.

Mr. Heydari refused. “I said, ‘No. I am the editor. I take full responsibility.’ ” Mr. Heydari says he told the men: “If I am arrested, the negative consequences will outweigh the effect of this photo.”

The chief agent backed off. Both men telephoned government and religious officials, and the judge who ordered the executions radioed the agent seated beside Mr. Heydari, the editor says.

Mr. Khalkhali, the judge, declared the photo a fabrication and told the agent to arrest the editor, Mr. Heydari says. He says he responded by offering to show the negatives to the agent “as long as you agree not to use force to confiscate them.”

The agent agreed and viewed the negatives with two fellow officials. “They were astonished,” recalls Mr. Heydari. The agent made another call and told Iran’s attorney general that “the newspaper has been considerate to only publish this one,” Mr. Heydari remembers. The agents left with one proviso: Upon their return from Kurdistan, Messrs. Bahrami and Razmi should come in for questioning.

THAT SAME DAY, Mr. DeSantis, the UPI editor, had prints of the photo distributed by motorcycle to the New York papers and by telephoto machine to thousands of papers across the country. On Aug. 29, the New York Times, Washington Post, Der Tagesspiegel in Berlin and the Daily Telegraph in London were among the many newspapers to run it. Nearly all credited UPI.

“Our play was fabulous,” exults Mr. DeSantis, now retired. “It was a once in a lifetime…. Like it was a movie set. One guy kneeling, aiming. One guy falling. A mass execution.”

Mr. Razmi remained in Kurdistan, where at a Sanandaj newsstand he came across a copy of Ettela’at featuring one of his other photos showing the blindfolded men standing in wait. He understood why his more incendiary photographs were unprinted but nonetheless was disappointed. “I expected my name to be published,” he says.

Two days later, reporter and photographer returned to the Ettela’at office in Sanandaj. The office manager lifted from his desk the Tehran edition of the paper that had reported the execution, they recall. He said copies brought to Kurdistan were selling for more than double the cover price. The manager was a Kurd and Mr. Razmi recalls him saying: ” ‘We have to build a statue of gold of you.’ And because of what he told me, I understood that this photo was dangerous.”

Close readers of Ettela’at could have surmised Mr. Razmi was the photographer. On Aug. 26, the day before the execution, the newspaper named him as one of three employees it had sent “to the Western portion of the country.” An Aug. 29, the day after the photo ran, the paper reported on its front page that he and Mr. Bahrami had been “sent to Kurdistan.”

Home in Tehran, after a long shower, Mr. Razmi spoke about the execution to his wife and again the next morning to curious colleagues in the newsroom. He says he asked Mr. Heydari why his photo had carried no credit and didn’t object when the editor explained his worry. “I told him jokingly that you would have also been executed in Kurdistan on the spot,” Mr. Heydari says.

Mr. Razmi walked to the newspaper darkroom and saw for the first time what had been the 18th exposure of his first roll of film. “There I realized what I had taken,” he says. Turning on the red safelights in the studio, the photographer made prints of eight stills and preserved on a contact sheet 27 of his 70 photographs.

Mr. Razmi asked the darkroom supervisor for his negatives and locked them in the middle of his three metal drawers together with his other prints. A few days later, he slipped the contact sheet and stills into the fold of a newspaper and hid them in his home, “somewhere no one would have noticed,” he says. The next morning, he returned to Kurdistan.

On Sept. 9, the Islamic Revolutionary Council published a notice in the Islamic Revolution newspaper: “we hereby draw your attention to the picture which was published on the front page of [Ettela’at] on 6/6/1358 and was objected to harshly by the public.” It continued: “If this occurs again, serious decisions will be made.”

A serious decision already had been made. The day before, the Foundation for the Disinherited — the holding company that in August had swallowed Kayhan, Iran’s largest paper — also seized Ettela’at. Overnight, the paper, privately held since 1920, became state-owned.

The image continued to spread. Reza Deghati, then 27, a free-lance Iranian photographer, had seen the photo. It is “the most stirring execution picture in the history of photojournalism, of the human being,” he says. Mr. Deghati says he procured five additional photos of the execution from an Ettela’at employee and mailed them to SIPA, the Paris agency that had been publishing his own photos since the revolution.

Goksin Sipahioglu says he received the prints from Mr. Deghati at his agency on Paris’s Rue Roquepine. Even though UPI had already published one, Michele Sola, photo editor of Paris Match magazine, paid 14,000 French francs (about $10,000 today) for the additional prints. Mr. Sipahioglu forwarded half that sum to Mr. Deghati in Tehran.

The magazine went on sale in Paris days before its Sept. 21, 1979, cover date. About 2,600 miles east, readers in Iran turned to page 66. Titled “Les Kurdes, sous les balles d’Allah” (“The Kurds, under Allah’s bullets”), the photos spread rapidly. People paid 20 times the cover price for the magazine, and dozens of Iranians tacked the photos about town.

No one, however, neither Mr. Razmi nor the Iranian brain trust, seemed to notice the magazine’s erroneous credit — “Reza (Sipa)” — printed in the lower left corner of the index page. “When someone sends a picture to us,” explains Mr. Sipahioglu, “we always credit him.”

Mr. Deghati says he sent SIPA a letter saying he didn’t take the photos and that SIPA sent out a news release via the AP retracting his name. Representatives at SIPA, Paris Match and the AP don’t recall Mr. Deghati clarifying the matter and didn’t find such a release in their archives.

Mr. Razmi returned from Kurdistan in late September and Mr. Ebrahimzadeh approached him at his desk. The photo editor asked for the negatives of the 70 photos and extended his hand. “I couldn’t protest,” Mr. Razmi says. “It belonged to him.” He unlocked his metal drawer. Mr. Ebrahimzadeh told the photographer the police wished to speak to him in Tehran’s Evin prison, Mr. Razmi recalls.

Mr. Razmi says he arrived at the prison with Mr. Bahrami and two Ettela’at editors, and quickly found himself alone with the late Asadollah Lajevardi, a future warden of the prison already notorious for torturing inmates. As part of his newspaper duties, Mr. Razmi had often photographed men housed in Evin whom the state would soon execute. “I had a right to be nervous,” he says.

Mr. Lajevardi asked him who had photographed the Sanandaj execution, Mr. Razmi says. When Mr. Razmi said he had, the guard asked why he had hidden his negatives in the drawer. “So that no one would take them,” Mr. Razmi recalls answering.

He told Mr. Lajevardi that he had permission from the judge to shoot the scene and that he hadn’t sent the pictures overseas. The interrogation was soft, and it became apparent to Mr. Razmi that he wouldn’t be harmed. Mr. Razmi returned to the paper, and a few weeks later was consumed with work when, on Nov. 4, Iranian students took hostages inside the U.S. Embassy.

The next month, UPI managing editor Mr. DeSantis sat down to submit his newswire’s best work of the year for awards. At the top of his list was the execution photo. “I was a very good picture editor,” Mr. DeSantis says, “but on this one you could be a dumb dog and pick this out.”

That neither he nor anyone at UPI knew who took the photo was of little concern. The agency had been the first to provide it to the press and presented it as the work of an unnamed UPI photographer, which, says Mr. DeSantis, he assumed it was. “It came on the UPI wire,” he explains.

“Because of the present unrest in Iran,” wrote the editor to the Pulitzer committee, “the name of the photographer cannot be revealed at this time.”

Mr. Razmi didn’t know his photograph had been nominated for the Pulitzer. He didn’t know the jury nominating finalists for Spot News Photography was overwhelmed by the entry UPI titled, “Firing Squad in Iran.” Robert Duffy, then an editor at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and chairman of the jury, says he informally lobbied a member of the Pulitzer Board that spring to pick the photo. “We were hell-bent on giving the prize to ‘Anonymous,’ ” he says.

On April 14, 1980, seven days after the U.S. severed diplomatic relations with Iran, ‘Anonymous’ won the Pulitzer Prize. Mr. Heydari told Mr. Razmi the news. But the same people who, in effect, had ordered the execution now owned his employer. Mr. Heydari says he was fired two months later. Representatives of the paper cancelled an August 2005 appointment at their Tehran head office and declined to be interviewed for this article.

Ettela’at didn’t report news of its prize-winning employee. Mr. Razmi says he “didn’t have the guts to celebrate.”

UPI did. The newswire flew its Tehran bureau chief Mr. Rizvi to the U.S. and had him speak to subscribers. “They were trying to show me off,” he says. Asked about the anonymous photographer, Mr. Rizvi recalls answering: “Eventually it will be revealed.”

IN THE SPRING, Ettela’at promoted Mr. Razmi, then 32, to photo editor. Iraq attacked Iran in September and Mr. Razmi covered the war. A mortar deafened his right ear in 1987. When months later Ettela’at asked him to work in Iraq, he decided he was tired of war. He quit his employer of 15 years, sold the home he had built by himself in a leafy neighborhood of northern Tehran, bought an apartment and opened a photography studio.

Forty years old, the photographer had come full circle, developing film and shooting portraits as he had as a boy. Says Mr. Razmi: “I was looking for a peaceful life.”

Mr. Razmi called the studio “Abgineh,” the Farsi word for glassware, which he says connoted for him the clarity of water. He didn’t advertise the studio. Still, six days a week, brides in gowns flocked to the shop, looked at Mr. Razmi and smiled.

Mr. Razmi thought often of Sanandaj. In his shop, he hung a large portrait of a boy wearing a Kurdish shawl and sash. Every summer, during the month of Shahrivar, he locked himself in his bedroom and looked at the execution photographs he had hidden.

On Aug. 3, 1997, three weeks before Shahrivar, Mohammad Khatami took office as president of Iran and hired Hashem Taleb to head his public relations. Mr. Razmi had met Mr. Taleb years before and saw a business opportunity. He drove to the office of the president, pronounced the headshots of Iranian officials unbefitting their rank and “suggested I take photographs of the president and the cabinet,” he recalls. Mr. Taleb hired him.

Days later, Mr. Razmi, the first “Official Photographer of the President and his Cabinet,” set up his flash umbrellas inside the Iranian presidential residence at the intersection of Palestine and Pasteur streets. He shot pictures of the new government. He developed the color portraits. Before mailing the prints to the president’s office, he stamped his name on the back of each.

The name Jahangir Razmi, however, remained unconnected to his most famous photograph. Monir Nahid, mother of two of the executed men, who has since settled in Los Angeles, says over time, “10, 20 people came to me and said, ‘I took the picture.’ ”

Among them, say Mrs. Nahid and her daughter, was Mr. Deghati, the stringer who in 1979 sent the photo to Paris Match. Mr. Deghati, who left Iran in 1981 and today lives in France working for Webistan Photo Agency, says he has never met the Nahids. Last September, Paris Match magazine quoted him saying he took the photo, adding in French that Mr. Khomeini “was furious.” Mr. Deghati says he knows Mr. Razmi took the photo, and that the magazine misquoted him.

Mr. Razmi says he first learned about a decade ago that others were claiming his work. Kaveh Golestan, Iran’s best-known photographer, reported to him that Mr. Deghati had said as much at a European photo exhibit. Mr. Razmi didn’t know that Mr. Golestan also had taken credit for the photo in classes he taught, according to several of his photojournalism students at Tehran University.

When Mr. Golestan died in 2003, after stepping on a landmine in Iraq, newspapers around the world reported that he had won a Pulitzer Prize. His widow, Hengameh Golestan, says her late husband never took credit for the photo and that the obituaries were mistaken. Mrs. Golestan says she knows Mr. Razmi took the photo.

On the fourth floor of a cement apartment building in northern Tehran, Mr. Razmi sat on a dimpled leather couch. His living room walls were barren of his work. Beside him on his couch, his son Ali sat rapt, tamping down a pinch of Cavendish tobacco in his father’s pipe. Mr. Razmi struck a match and puffed.

“My sons have told me a lot of times that I should go and prove that I am the photographer,” Mr. Razmi said, his voice soft and his eyes cast down. “I said, ‘No. Better not.’ ”

It is understandable why he feared claiming credit for such a public indictment of the Islamic Revolution. The hardline Mr. Ahmadinejad, elected in June 2005, shuttered Shargh, the country’s last large reformist newspaper, three months ago. Mr. Razmi also was still the official government photographer and returned the next morning to the presidential residence to shoot Mr. Ahmadinejad’s cabinet, including the defense minister who in 1979 helped quell the Kurds.

But Mr. Razmi, who is now 58, said part of him always wanted to step forward. He was disappointed when he first saw that his photo didn’t carry his name. He was irked when others took credit, people who “never feel the danger,” he said. And all the time, he was weighted by his secret, that of an ordinary man witness to extraordinary events. “Without this picture,” he said, “I wouldn’t be anything.”

Emboldened by time and dismayed by the opportunism of his fellow photographers, Mr. Razmi decided the moment was right to tell his tale after this newspaper approached him. “My name should be there,” he said.

Minced lamb and baghali polo — a dish of green rice and beans — awaited Mr. Razmi at home, and he sat down to eat with his wife and sons, his sister, two nephews and his father-in-law. They talked about Mr. Razmi identifying himself, for the first time, as the anonymous photographer.

Mr. Razmi had done nothing wrong, they reasoned. He photographed the execution with the permission of the judge. He turned over his negatives to the photo editor. He described his work to the prison guard. He wasn’t the one who sent the six images abroad. He didn’t earn a single rial or credit from his photo, the rights to which had passed from UPI to the Bettmann Archive to Corbis Corp.

The family approved of his decision to come forward. Voicing hope that it wouldn’t harm Mr. Razmi, eight people around the table spoke as one: “Inshallah,” if Allah wills it.

Past midnight, Mr. Razmi retreated to a bedroom closet and lifted his canvas camera bag by the faded strap that had hung over his shoulder during the 1979 revolution. Here in pale black ink on the inside flap of a pocket was written in Farsi, “Jahangir Razmi, Ettela’at, 328 331” — the newsroom number to phone in the event of his death.

Mr. Razmi returned to his living room. He had unearthed his contact sheet and stills for his annual look back at the execution. “I have pictures that have never been published,” he said.

The photographer held in his right hand a sheaf of black-and-white photographs, 27 images that were 26 years, five days old. He withdrew from a plastic sleeve a furling photo of the sandwich maker who cried as he waited to be shot.

Mr. Razmi thrust it forward. “Who has this picture?” he asked, his voice rising. “Nobody.” He thrust forward a photo of the dust that rose over 11 fallen men. “Who has this picture?” he asked. “Nobody.” He thrust forward a photo of the bodyguard surveying the men he had shot. “Who has this picture?” he asked. “Nobody.”

Mr. Razmi returned the photos to the sleeve that had held them since 1979. And for the first time since he had secreted them home in a folded newspaper, he put them in a Samsonite briefcase he had long used to store chosen photos from his career.

Says Mr. Razmi: “There’s no more reason to hide.”

Copyright © 2006 The Wall Street Journal. All Rights Reserved.

Click images to zoom